A Tale of Two Hoodies: The Geodivide over Nike Tech Fleece

In a bittersweet reminder of Twitter B.E (B4 Elon), Central Cee's claims that he made Nike Tech popular in the US launched a cultural skirmish between Londoners and New Yorkers over who did it first.

Yo, people! Welcome back to RADIO KNIFE. My (hopefully) twice-weekly set of thoughts featuring angles and perspectives on culture, brands and consumer behaviour that even a cartographer would struggle to locate. Knives out. 🤺!

All you readers support RADIO KNIFE. Help yourselves, subscribe to stay inside—it’s freezing out there.

“Then tell the Wind and Fire where to stop, but don’t tell me.” - Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities.

London and New York, are two great, elemental cultural engines. Two of the four ‘‘alpha cities’’ - with Paris and Tokyo the others. On any given day London is wind, and New York is fire. Or vice versa. Producing broad, all-encompassing, and far-reaching global impact. So much so that at times - it’s difficult to locate the eye of the trend’s storm or the source of the kindling. This weekend’s furore over which city did Nike Tech (Fleece) first was one of those times.

The soundbite, ostensibly, started the blaze over the weekend. Still, it prompted me to consider a deeper investigation into the flow of influence behind Nike Tech’s rise in popularity, how cities’ youth and subcultures popularised it to become a fixture in global culture, and, more interestingly, whether the idea of proximal taste is even possible in the hyperlinked world of 2025.

The OG Nike Tech Pack dropped in 2007. It was born as a modern revamp of the classic Nike Windbreaker, copying its iconic design but redeveloping it using "no sow technology," which gave it a more streamlined, minimal technical aesthetic. Upon release, the windbreaker became an immediate staple in London. It was viewed as an elevated spin on the classic Nike tracksuit.

The long-established relationship between London and sportswear starts with the tracksuit, specifically the Nike tracksuit. The one Dizzee donned on the cover of Boy In Da Corner in 2003. Which was the first major global musical moment for Grime and for Black-British youth. That decision was intentional: the tracksuit represented the attitude and psyche of a generation and Dizzee wanted to make it clear who he spoke for.

This is at the heart of the debate and is the core impetus behind us Londoners feeling ownership over Nike Tech, Londoners are claiming the cultural meaning behind the tracksuit’s popularity. The tracksuit represents the angst, the persecution, rebellion and finally, the overcoming of a generation - exemplified by Central Cee wearing Nike Tech on the red carpet at the 2022 Fashion Awards. Though Cench isn’t an artist of the same calibre as Dizzee or one who faced the same social inequities, he is a star born of London’s lineage - made possible by Dizzee and his cohort’s work - and is now the global flagbearer for London’s youth culture.

That Fashion Awards moment once again shows why the tracksuit, as a cultural icon, is one unique to London, the UK and Europe more broadly. In a way that New Yorkers, or Americans at large, cannot claim. The tracksuit was invented by Le Coq Sportif in 1939 - as a ‘‘Sunday suit’’ - athleisure before the moniker?. The idea was then built on by adidas in the 60’s, which is when it first began its long trajectory in UK culture. According to Dr Joanna Turney, Design Historian and associate professor of Fashion at Winchester School of Art:

The tracksuit developed primarily as a sub-cultural item in the UK in response to two things; the Smith and Carlos Black Power salute at the Mexico City Olympics 1968 and Bob Marley’s Jamaica tracksuit.

In the UK, the tracksuit’s relevance is firmly rooted in class divides, sociopolitical leanings, and music. An accurate parallel is the baggy jeans made popular by black and brown inner-city American youth and artists. Covered by Hiram Rabell-Ramos on fastatUCLA, baggy jeans are a style inspired by the "Zoot Suit" - a long-standing icon of black and brown American fashion—made popular by Jazz musicians as a representation of their free-wheeling, rebellion against White American norms and inequality. This is not something Londoners could claim.

These aren’t just vague debates over trends; they’re discussions about cultural armour, tools used by marginalised groups to persist against persecution.

Now back to Tech Pack. In 2007, at the time of the original Nike Tech release in London, Nike’s cultural capital was unmatched—and having a Tech Pack windbreaker meant your sauce was, too. But with the original ‘07 release, its true power was only teased. It would take a subtle change of material for its impact to materialise.

The real shift began in 2013 when the Tech Pack was updated to include Nike Tech Fleece. This collection had been designed alongside some of Nike’s top athletes (Nike-era Neymar 🐐) to ensure the collection had its roots firmly in performance, but with a future-forward focus on fashion.

And this is where the cross-Atlantic cultural charades began. Nike Tech’s idea of fusing well-cut, neat design mixed with cosy performance technology was a primary driver behind two of the last decades’ biggest trends - athleisure and techwear. This is the angle New Yorkers were trying to claim Nike Tech from. They were looking at Nike Tech as a global trend, wrongly treating the London argument as a microcosm for sportswear culture at large and confused the debate into a discussion of: WHO’S CULTURE IS MORE POWERFUL?

America has 11 states that are bigger than all of the UK. London is just about the same size as Chicago, the third-largest city in the states. Our friends on the NYC side were conflating scale as a means for an uncontestable, ‘‘source code’’ type of cultural relevance. Ah, patriotism, yes patriotism, will do that.

But Londoners weren’t playing the numbers game. We can’t win that. We were talking about the meaning and representation of the inner-city attitude and its subcultures, that is the relevance of the tracksuit in a Black-British and UK context.

New Yorkers adopted the aesthetic from us without recognising the layers of lived experience that make it more than a trend to Londoners. Tracksuits, Nike Tech Fleece, represent a lifestyle and it represents history. To those stateside, it’s athleisure, it’s techwear, it’s just a trend. But to Londoners, we’re talking about a core conduit to our experiences in the city and the world.

In debates like this, the adhesive parts end up getting lost. Because London and the UK are geographically smaller, our tastes, trends, and norms are examples of what I describe as "proximal taste"—ideas with which full meaning is limited by proximity. So when they enter global culture, the meaning can fray, creating a need for Londoners to represent our traditions, as Central Cee and the likes of Skepta have plenty of times before.

A crossover, flipside moment to Central Cee’s statement, could be Bella Hadid essentially introducing the Air Max 95 as an IT shoe in the US on Complex’s Sneaker Shopping. At the time, this moment and the memes spiked a new wave of demand stateside for the 95, known by Londoners as the 110.

Here is an American popularising a shoe which is just as synonymous with London, as tracksuits are. Liking the shoe, but not recognising why they’re popular. That wouldn’t happen with Jordans (obviously, but you get my drift). You can’t expect everybody to recognise or know the history of a subculture or trend, but this is why Londoners will represent it loudly - and will correct confusion over the flow of influence, as we did over the weekend.

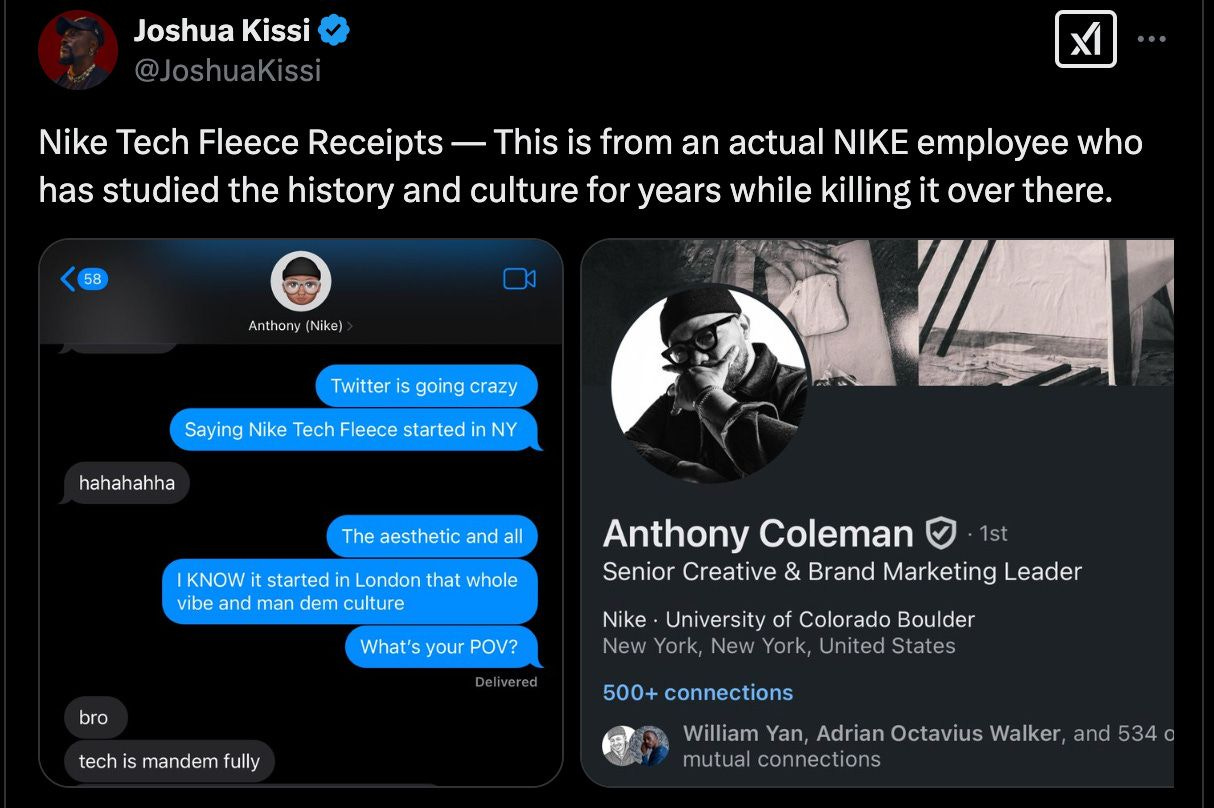

Like Joshua Kissi said…

‘‘America may have the loudest voice in media and global relevance, but that doesn’t mean it holds the sole authority over culture for everyone else.’’